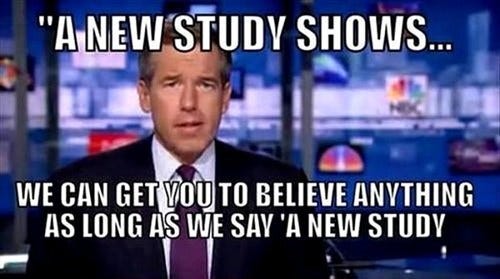

We’ve probably all had our fill of studies. How many times have you heard, “I read a study that showed..” in the last few years? During the pandemic, trading links to studies seemed like it was a national pastime. Maybe the keyboard warriors can still stomach diving into the granular and the tabular, but I suspect a lot of us are happy to leave them to it for a while. To be sure, I am ever grateful for those who read through pages of research, bravely screenshotting and posting inconvenient facts about death and tyranny before the study, the author and his dog were all cancelled by our public health overlords. If accountability for that malpractice is ever forthcoming, those receipts will be useful.

Experts told us lockdowns, masks and vaccines were good for us, with studies trotted out to back their claims. But as we know, research was cherry-picked depending whether it reinforced the right narrative or not. The pandemic showed more clearly than ever that when it comes to research papers, mileage may vary – some studies simply aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. Especially when the situation is ideological, urgent or lucrative, research papers are just as flawed as the fallen humans who write them.

News about studies has hit the headlines again with two stories. The first headline claimed that a “wave” of retracted papers is “shaking” the world of physics. Claims about “major breakthroughs in quantum computing and superconducting research” have been walked back after other researchers could not replicate the results.

While a number of retractions are due to fraud, some are evidence that the scientific community is working as it should – the researcher may have been a little carried away with his own ideas, but “having made or being informed of an honest mistake, and upon reflection, [now] feel[s] they can no longer stand behind the claims of the paper.” With very sophisticated or intricate experiments, it is understandable how reproducibility could become an issue. One scientist noted that when he “revisited his own published work from a few years ago, sometimes he’s had trouble recalling how his former self drew those conclusions because he didn’t leave enough documentation.“

All well and good.

But some retractions are triggered by more nefarious actions. Another recent headline said that old and esteemed academic publisher Wiley announced that it was shutting down 19 journals after a “massive influx” of fake papers. According to Retraction Watch, the journals in question were acquired when Wiley bought Cairo-based publisher, Hindawai, in 2021.

Those who have taken interest in keeping researchers accountable pointed to the fact that Hindawai had embraced a novel editorial model where a journal “invites a scholar or group of scholars to serve as guest editors for a specific issue of papers on the same topic or theme.” This model, “popular among questionable journals,” is now being used in more reputable publications, according to the George Washington University blog. Switching out who heads up the curation gives more scope for innovation and cross-disciplinary cooperation, but the Guest Editor Model also leaves room for fraud and marketing to academics. (There’s a paper about that.)

Another problem facing publications is straight up fake papers. Wiley also retracted over 11,000 papers associated with “paper mills”, sketchy places which churn out fabricated studies. GWU blog explains, “In the early days of paper mills, plagiarism was the biggest concern. However, paper mills have become more sophisticated and are now capable of fabricating data, and images, and producing fake study results.” China and Russia are frequently blamed for producing the majority of junk studies.

There is also the “publish or perish” model of academia which means that in order to secure tenure, the professoriate must be constantly writing papers. All of this writing of books means that sites dedicated to sorting and indexing papers have sprung up alongside academic publishing. Cue the Web of Science, “the world’s oldest, most widely used and authoritative database of research publications and citations.” Papers are grouped according to their field and affiliated institution and ranked for their “impact” according to a tally of citations. Having the citation tally for your paper at the top the leaderboard is quite prestigious.

And finally, there is the potential for mischief in the process of peer review. During covid, the objection that “it’s not peer-reviewed” was a get-out-of-conversation-free card when it came to discussing the pandemic. But according to an article I found, peer review is no longer the gold standard it claims to be (if it ever was). Author Niall McCrae and seasoned researcher Professor Gloria Moss argue that the peer review process is actually a bit of a black box. They write:

“Until at least the 1950s, the decision to publish was made by the editors of academic journals, who were typically eminent professors in their field. Peer review, by contrast, entails the editor sending an anonymized manuscript to independent reviewers…This may seem fair and objective, but in reality peer review has become a means of knowledge control – and as we argue…perhaps that was always the purpose.”

McCrae and Moss go on to tell the intriguing tale of Robert Maxwell’s rise to wealth and status as a publishing mogul. The father of Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein’s former flame, purchased an old British publishing house and renamed it Pergamon Press (hmm..). Maxwell pioneered peer review, installing it as standard at most of his journals but McCrae and Moss argue that the system means “opportunities for writers with analyses or arguments contrary to the prevailing narrative are limited. [Peer review becomes] a regime to reinforce prevailing doctrines and power.” According to the article, it was Maxwell’s ambition to monopolize the publishing industry with the “goal of a globally controlled academic press.” His famously shadowy links to intelligence agencies in a number of countries may have helped him out with that project.

Knowledge is power, as they say. One man looks closely at the world and is humbled by what he finds, applying his learning to solve human problems. But another sees his discovery (or indeed falsified discovery) as a means to subjugate and control. The panic over “misinformation” reveals some of that spirit. The desire to “protect” people from dangerous information may be a valid concern, but the difference between allowing people to discern true from fake and wielding safetyism as cudgel to enforce compliance is a significant one. It is the difference between treating citizens like adults or like children. Or worse, as pawns.

If you are able to understand the minutiae of public health research or the complexities of information systems or the nuances of climate data or discern propaganda in transgender literature or grasp patterns in economy, or any other expertise, you have an important role to play. In an age where decisions which affect many families, churches and communities are purportedly based on research, Christian thinkers are at the coalface when it comes to parsing arguments for the sake of those who cannot. C. S Lewis writes in his essay “Learning in War-Time” that:

“To be ignorant and simple now—not to be able to meet the enemies on their own ground—would be to throw down our weapons, and to betray our uneducated brethren who have, under God, no defence but us against the intellectual attacks of the heathen. Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered. The cool intellect must work not only against cool intellect on the other side, but against the muddy heathen mysticisms which deny intellect altogether.”

In the end, it is enough to know that science is one way of understanding God’s world. But it is not the only way. Scoffers will demean God’s word because it is “not a science textbook”. Yet even simple ones can be comforted that it contains all we need for life and godliness, as St Paul says. Knowledge is handy, but wisdom is better. The Preacher, the wisest ever to live wrote that seeking to understand the world is a “burdensome task God has given to the sons of man.” Accordingly, he set himself to study; “I applied my heart to know, to search and seek out wisdom and the reason of things”, as he writes in the book of Ecclesiastes. Yet for all his effort, he found that some mysteries belong to God.

We need not dismiss all scientific research, nor be overly burdened with trying to understand it all. We only need to be ones who have our eyes open.